Mountains dominate the landscape, traversing the center of the country, running generally in a northeast-southwest direction. More than 49 percent of the total land area lies above 2,000 meters. Although geographers differ on the division of these mountains into systems, they agree that the Hindukush system, the most important, is the westernmost extension of the Pamir Mountains, the Karakorum Mountains, and the Himalayas.

The origin of the term Hindukush (which translates as Hindu Killer) is also a point of contention. Three possibilities have been put forward: that the mountains memorialize the Indian slaves who perished in the mountains while being transported to Central Asian slave markets; that the name is merely a corruption of Hindu Koh, the pre-Islamic name of the mountains that divided Hindu southern Afghanistan from non-Hindu northern Afghanistan; or, that the name is a posited Avestan appellation meaning “water mountains.”

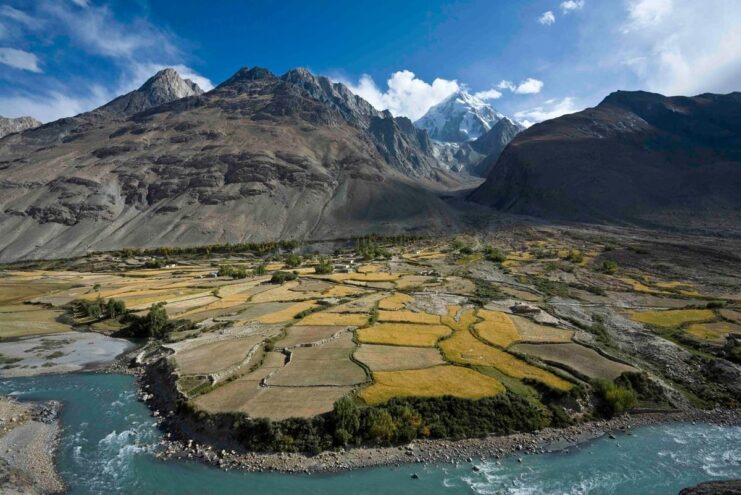

The mountain peaks in the eastern part of the country reach more than 7,000 meters. The highest of these is Nowshak at 7,485 meters. Mount Everest in Nepal stands 8,796 meters high. The Pamir mountains, which Afghans refer to as the ‘Roof of the World,” extend into Tajikistan, China and Kashmir.

The mountains of the Hindukush system diminish in height as they stretch westward: toward the middle, near Kabul, they extend from 4,500 to 6,000 meters; in the west, they attain heights of 3,500 to 4,000 meters. The average altitude of the Hindukush is 4,500 meters. The Hindukush system stretches about 966 kilometers laterally, and its median north-south measurement is about 240 kilometers. Only about 600 kilometers of the Hindukush system are called the Hindukush mountains.

The rest of the system consists of numerous smaller mountain ranges including the Koh-e Baba; Salang; Koh-e Paghman; Spin Ghar (also called the eastern Safid Koh); Suleiman; Siah Koh; Koh-e Khwaja Mohammad; Selseleh-e Band-e Turkestan. The western Safid Koh, the Siah Band and Doshakh are commonly referred to as the Paropamisus by western scholars.

Numerous high passes (kotal) transect the mountains, forming a strategically important network for the transit of caravans. The most important mountain pass is the Kotal-e Salang (3,878 meters); it links Kabul and points south to northern Afghanistan. The completion of a tunnel within this pass in 1964 reduced travel time between Kabul and the north to a few hours.

Previously access to the north through the Kotal-e Shibar (3,260 meters) took three days. The Salang Tunnel at 3363 meters and the extensive network of galleries on the approach roads were constructed with Soviet financial and technological assistance and involved drilling 1.7 miles through the heart of the Hindukush.

Before the Salang road was constructed, the most famous passes in the Western historical perceptions of Afghanistan were those leading to the Indian subcontinent. They include the Khyber Pass (,1027 meters), in Pakistan, and the Kotal-e Lataband (2,499 meters) east of Kabul, which was superseded in 1960 by a road constructed within the Kabul River’s most spectacular gorge, the Tang-e Gharu. This remarkable engineering feat completed in 1960 reduced travel time between Kabul and the Pakistan border from two days to a few hours.

The roads through the Salang and Tang-e Gharu passes played critical strategic roles during the recent conflicts and were used extensively by heavy military vehicles. Consequently, these roads are in very bad repair.

Many bombed-out bridges have been repaired, but numbers of the larger structures remain broken. Periodic closures due to conflicts in the area seriously affect the economy and well-being of many regions, for these are major routes carrying commercial trade, emergency relief and reconstruction assistance supplies destined for all parts of the country.

There are a number of other important passes in Afghanistan. Wakhjir (4,923 meters), proceeds from the Wakhan Corridor into Xinjiang, China, and into Kashmir. Passes that join Afghanistan to Chitral, Pakistan, include the Baroghil (3,798 meters) and the Kachin (5,639 meters), which also cross from the Wakhan.

Important passes located farther west are the Shotorgardan (3,720 meters), linking Logar and Paktiya provinces; the Bazarak (2,713 meters), leading into Mazar-i-Sharif; the Khawak (3,550 meters)in the Panjsher Valley, and the Anjuman (3,858 meters) at the head of the Panjsher Valley giving entrance to the north.

The Hajigak (2,713 meters) and Unai (3,350 meters) lead into the eastern Hazarajat and Bamiyan Valley. The passes of the Paropamisus in the west are relatively low, averaging around 600 meters; the most well-known of these is the Sabzak between Herat and Badghis provinces, which links the western and northwestern parts of Afghanistan.

These mountainous areas are mostly barren or at the most sparsely sprinkled with trees and stunted bushes. True forests, found mainly in the eastern provinces of Nuristan and Paktiya, cover barely 2.9 of the country’s area. Even these small reserves have been disastrously depleted by the war and through illegal exploitation. The forests are in fact in a crisis situation. A 1996 a FAO report estimated that of the 4.7 million acres of forests existing at the beginning of the war, in 1979, considerably less than one million acres survive today.